During the 19th century, the small town of Fray Bentos, in western Uruguay, was heralded as “the great kitchen of the world.” The industrial site exported more than 200 meat products across the globe, especially corned beef and steak and kidney pies. In 2015, this history earned the site UNESCO World Heritage status. It wasn’t just a preeminent food supply hub—it developed technologies that were adopted worldwide.

The town of Fray Bentos was founded in 1859, first as Villa Independencia. The area—near a river basin bordering Argentina—featured swathes of cattle grazing neighboring grasslands. An Englishman, Richard Hughes, bought the area in 1859 for salting meat.

But the site didn’t become an industrial meat powerhouse until the 1860s, when Georg Giebert, an engineer, bought the land. He founded Giebert et Compagnie (later known as the Liebig Extract of Meat Company). Giebert liked that the Uruguayan site had its own harbor, where workers could export products around the world, and he saw that there were cattle being slaughtered for their hides alone. (It was also far less expensive to raise cattle there than in Germany.) As UNESCO notes, the complex’s location adjacent to “prime, fertile land conducive to cattle-raising and agricultural production” made it unique. So Giebert brought over machinery from Scotland, then began breeding cattle and producing meat in new ways.

The site’s first great hit was a meat extract. It was developed in Europe, when Justus von Liebig, a German chemist, created a meat extract as cheap fare for destitute Europeans. To do so, he took cuts of meat and boiled them down in water, producing a kind of tonic that then hardened. He developed it in Munich, but without commercial prospects (German beef was too expensive), he offered his meat tonic formula to anyone who could produce it. Giebert contacted him, and Liebig moved to Uruguay, where he became the plant’s first scientific director. In an era where refrigeration was not standard, and sanitation problems were common, Liebig’s invention found fans. It even made an appearance in Jules Verne’s From the Earth to the Moon. In the novel, astronauts nosh on beef extract during their cosmic journey.

Yet making meat tonic required a ton of beef. As Argentina Independent notes, one kilogram of tonic required a whopping 32 kilograms of beef. By using technologies such as chutes, pulleys, and an elevated floor structure—a huge novelty at the time—the company became an industrious meat processing plant, both in terms of speed and in using every part of the buffalo, so to speak. At its peak, the factory could process one cow in five minutes. Previously, the town had “only slaughtered the cow for its hide, tongue, and some cuts of meat,” as Rene Boretto, a historian, told the BBC. Blood was repurposed as organic fertilizer, hair was refurbished into brushes, and hooves were made into glue. The company even sold bile stones to the French perfume industry.

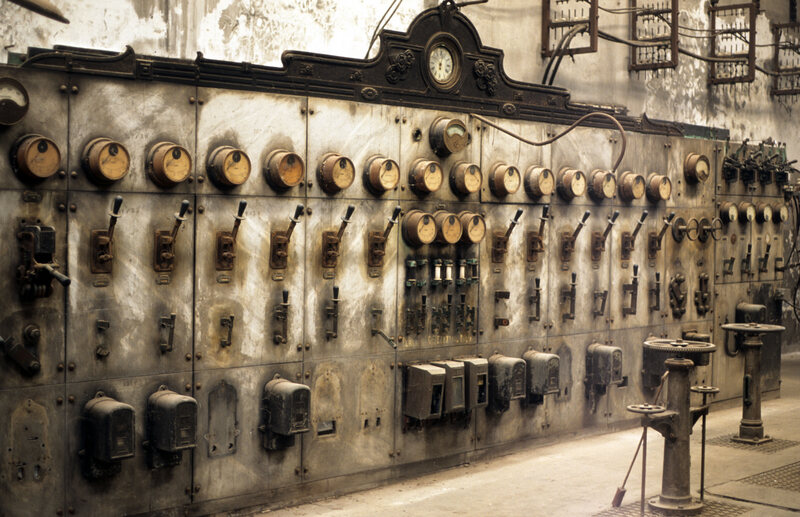

Yet it was von Liebig’s other’s invention, tinned corned beef, that became iconic. Twenty years after it opened, the factory experienced such high demand from exporters, especially in Europe, that it had workers from over 50 countries on staff. In 1924, it changed hands to British owners, becoming Frigorífico Anglo Del Uruguay. Eventually, an entire community cropped up around the plant, complete with housing, workers’ cooperatives, an English school, and sports facilities. At one point, the factory employed 5,000 people, nearly half of the town’s population of 12,000. It had electricity three years before Uruguay’s capital, Montevideo.

The company’s revolutionary approach was—like Henry Ford’s automobile factories—to centralize production. The livestock grazed nearby, workers processed and packaged everything on site, and the company even managed how their products were exported on their docks. Soon enough, similar techniques appeared elsewhere. In 1915, the sizable Frigorífico Puerto Bories factory opened in Chile. It was the first industrial site to process sheep, and it had similar workers’ accommodations and state-of-the-art facilities. (The site is now an industrial museum.)

Fray Bentos’s ability to mass produce corned beef—as well as its portability in cans—made its products ideal war fare during the First and Second World Wars. As CNN notes, the rate at which the company exported its food to Europe during the impoverished time caused it to be known internationally as the nation of “fat cows.”

The term “Fray Bentos” also crept into the soldiers’ slang. “In World War I, soldiers would say ‘Fray Bentos’ to indicate that something was good, the same way we nowadays say OK,” said Boretto. In her book A History of Cant and Slang Dictionaries: Volume III: 1859-1936, Julie Coleman writes that the term arose out of a play on “très bien,” the French way of saying “very good.” Julian Walker, author of Words and the First World War: Language, Memory, Vocabulary, writes that this was likely borne out of a larger practice of the English teasing French soldiers by punning words, sometimes earnestly and sometimes more maliciously. In this particular case, the term “très bien” evolved into “tres beans,” which eventually became “Fray Bentos.”

This embrace is ironic, considering how much British troops loathed the “bully beef” rations, along with hard biscuits and marmalade, that they were rationed. The corned beef, under the auspices of the British-owned company, also then became a staple for people living overseas during the wars.

The factory closed its doors in 1979, but is still making wartime headlines. Earlier this year, a story surfaced from historians at the Tank Museum in Dorset, England, about an abandoned tank crew whose tank became stuck in mud during the Second World War. Eight of the nine British soldiers stood their ground for three days, dodging attacks from German troops, at the Battle of Passchendaele in Belgium. They were known as the Fray Bentos boys—so named because before the war, their captain had a license to sell Fray Bentos. Inside the tank, they felt not unlike the famed tinned meat they’d been eating.

While the meat products are still produced in the UK, the structures in Fray Bentos that once housed workers and meat-processing tools are immortalized these days in the Museum of the Industrial Revolution, which charts the simultaneous growth of the factory and the town. Some inventive locals have even been putting it on contemporary menus. The Fray Bentos complex was recognized by UNESCO in 2015 for its contributions to meat processing technology—and for beefing up what we think of as slang in the process.

Gastro Obscura covers the world’s most wondrous food and drink.

Sign up for our email, delivered twice a week.

Bagikan Berita Ini

0 Response to "How a Uruguayan Meat Factory Became Iconic Worldwide"

Post a Comment